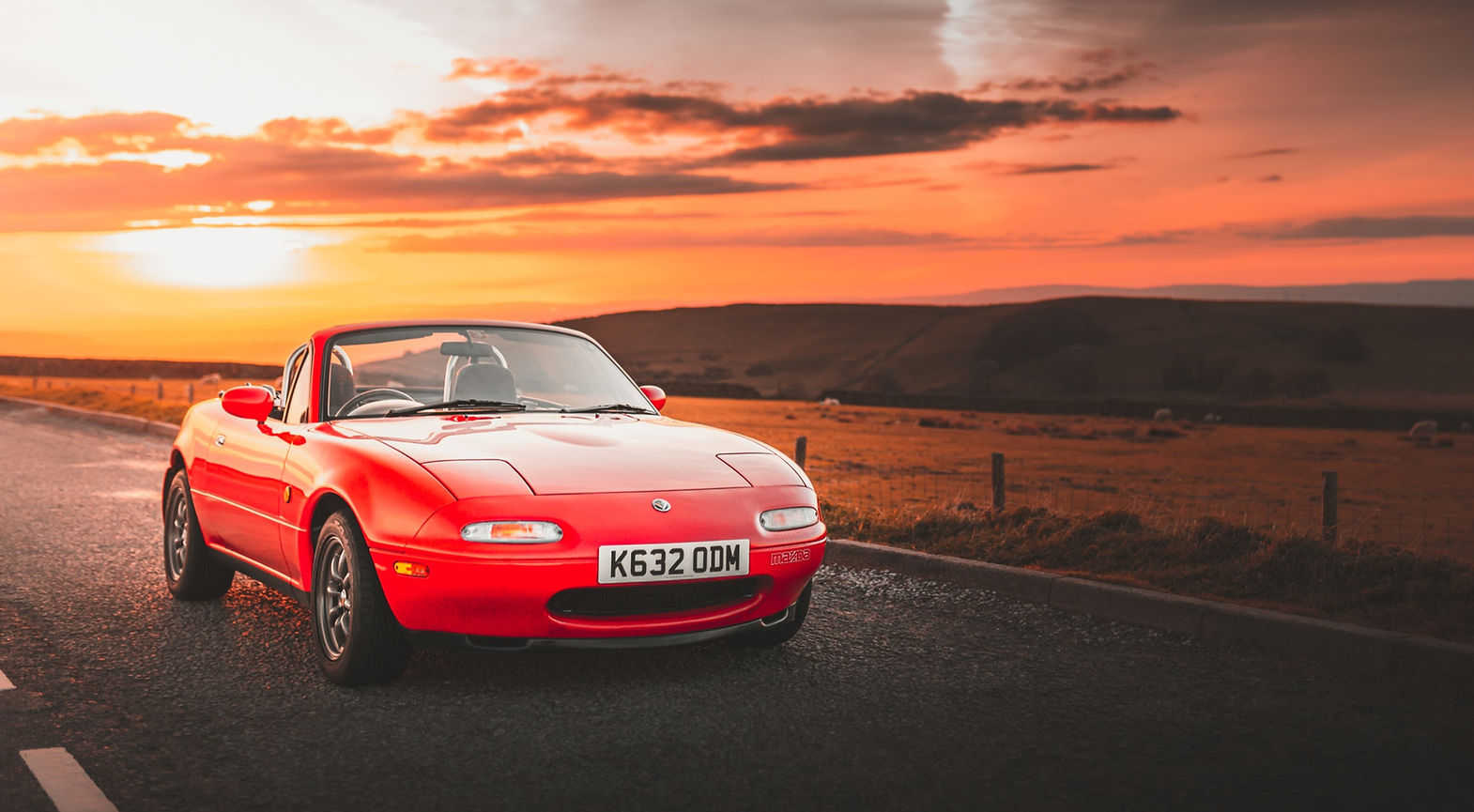

Back to the Future – MK1 Mazda MX-5 Review

With the thrill of driving under greater scrutiny than ever, John Bee tackles the average speed-monitored Cat & Fiddle pass in a mk1 MX-5 and ponders what the future holds for the car enthusiast.

Around 7,000 speed cameras are watching over us here in the UK. That’s approximately 900 more than the entire United States. Just let that sink in for a second – a country with a mere 262,000 miles of road has more than a country with 4,100,000.

In the coming years that number is only going to increase. Profits from tactically placed cameras are hard to ignore for cash-strapped councils and quite often, it’s irrelevant whether or not they actually reduce accidents. Speed cameras are just another tug of the ever-tightening noose around the neck of people who drive for enjoyment. We’re vilified by the health and safety conscious for speeding, public enemy number one for the environmentalists and an easy target for exploitation by governments looking for extra income.

Where does this leave the petrol head? In a world where you can buy a hot hatchback with over 400 bhp, you start to think, what’s the point? How can one still enjoy the beauty of the British countryside and a favourite back road if Big Brother is standing over you like a vulture? Should you dare depress the throttle for any longer than six seconds, you’ll have points on your licence and a fine.

The answer lies in finding a car with solid fundamentals. A car that feels alive at double-digit speeds, not triple figures. One that makes use of the elements, with tight gearing and a sweet, rev-happy naturally aspirated engine. Get the basics right and waking up early to catch the sunrise along your favourite B road doesn’t have to be a thing of the past.

It’s why we’ve come to the cat and fiddle pass in the Peak District, a once famous driving road now lined with the yellow pylons of doom, armed with an early Mazda MX-5 to challenge the naysayers proclaiming the end is nigh. We’re looking to strip away the excess and lean on the fundamentals of the physical act of driving.

When I talk about fundamentals, I’ll give you this analogy. In boxing, the sweet science, you’re first taught footwork. The ability to close in on an opponent and get yourself out of trouble when needed is a skill you must master before you’ve even thrown a punch.

Only when you’ve conquered keeping your balance do you move on to throwing your first and most important punch, the jab. The jab serves as a rangefinder, a stinging snapshot or a distraction. It’s your closest weapon to the fighter standing in front of you. Without learning these basic fundamentals, your style will be flawed.

A natural ability of power, speed or reflexes can mask a lack of basic skills to a degree but you’ll be found out eventually. What use is power if you can’t land a shot? What use is speed if your opponent is timing you coming in? And what use are those reflexes if you’re off balance?

The same fundamental rules govern building a sports car. Mazda took the blueprint of the Lotus Elan and applied the Japanese philosophy of Jinba Ittai, “reflecting the feeling that the sense of oneness between a rider and his beloved horse is the ultimate bond.”

It translates to the universal sports car language of an engine at the front, driven wheels at the rear for balance, a raspy twin-cam engine for power and fully independent suspension at each corner for handling. Not only did they use the Elan recipe, but they also made it reliable.

This made the MX-5 a formidable rival for any manufacturer looking to move in and take a slice of its profits. Many came to the fight already at a disadvantage using an adapted platform from a mundane hatchback and scraps from the manufacturer’s parts bin.

Today, the MX-5 is part of the motoring landscape, but wind the clock back to 1989 and the roadster market was dead on its knees. In Japan, your only option was the Alfa Romeo Series 3 Spider, carrying typical reliability shortcomings and a platform that could trace its roots back three decades, complete with a live rear axle.

It was a massacre – the Mazda breathed new life into the division and suddenly manufacturers were pulling their heads out of the sand. By 1995 challengers were lining up for their shot at the title, but all entered the ring with one hand tied behind their back. Fiat returned with the pretty Barchetta, but it was now front-wheel drive, as was the next-generation Alfa Spider. Just like that the Italians – long the custodian of the small roadster – effectively threw in the towel.

Even the Germans got in on the act with the trailing arm BMW Z3, force-fed to us by an utterly underwhelmed James Bond. Mercedes introduced its SLK sporting a unique folding metal roof – both the cars’ USP and Achilles heel as the weight hampered dynamics. MG had dusted off the cobwebs in 1993 with a revived B from the 1970’s. The British firm took their ‘95 effort seriously with the F, a mid-engined, rear-wheel drive arrangement complete with fizzy K-series engines and Hydragas suspension.

Sadly, the MG still couldn’t quite take the fight to the Mazda, but the one car that did from behind the wheel – the MKIII Toyota MR2 – finally arrived in 1999. It’s not hard to see why the MX-5 set production records for a two-seater car – it took the industry a decade to come up with a genuine title challenger.

Interestingly, there was almost a point where the MX-5 suffered a similar fate at the hands of the bean counters. The MX-5 as we know it was one of three initial design concepts – a front-engine, front-wheel drive version by one design studio in Japan, a second Japanese design that was mid-engined, rear-wheel drive and a front-engine, rear-wheel drive by Mazda’s Californian studio. It was in August 1984 when the three models were built in clay that “Duo 101” the Californian code name, won the competition. Final approval was granted at the start of 1986 and it moved into the production phase with test mules being created.

Rumours have circulated that the initial design didn’t have independent rear suspension but after making some calculations, the car proved cheaper than expected to produce. Mazda decided to use that budget and go all out with double wishbones on all four wheels, showing confidence and commitment to the project that many other companies would not have made. Can you imagine what British Leyland would have done? Pocketed that extra cash for the director’s Christmas party most likely!

This particular JDM Eunos Roadster belongs to Anthony Gibbons. His car is a fine example of the breed, a Japanese import with a light and free-revving 1.6 DOHC engine, mated to a short-throw manual box, arguably the best combination in an NA. Some tasteful RS Watanabe F8 wheels give it a more purposeful look but it’s kept pretty much standard and all the better for it. The original MX-5 is a truly timeless and iconic design. The simple, no-nonsense interior is a far cry from the screen-covered dashboards of today. There’s no distraction from what you’re here to do, drive.

Like with boxing, huge power is pointless if it can’t be put to the tarmac. By increasing the power you’re raising the speed required for the driver to find a car’s limit, great on track but on the beautiful but average-speed camera-laden road around the Cat and Fiddle Inn, not ideal. This is where all 115 bhp of the Mazda’s sweet, revvy engine came into its own. I was able to wring its neck, taking in the noise and vibration of a car working with you to deliver a pure driving experience at speeds less likely to trouble the old bill.

Why is it “pure?” Simply because that lack of torque means you need to keep a flowing pace, your mistakes aren’t masked by a shove of your right foot making up time on corner exit or where you went wrong on entry. You need to read the road ahead, get into a zone and plan your braking points carefully. Getting back on the power early and letting the supple suspension compress, you feel the outside rear tyre take the load and glide you around the corner.

It’s this inherent chassis balance coming from the fully independent suspension and near-perfect weight distribution that means you’re never fighting the car, there’s no scrabbling for grip or sudden, snap oversteer. It teaches you to become a better driver, more attentive, more focused and more at one with the machine but in a calming way. If the car could talk to you, its voice would be that of a soothing-sounding woman, making you feel at ease while you got on with the job at hand. The mechanical interaction extends to the gearbox, a beautiful short throw with a positive action. The only thing that ages the driving experience is the subpar braking power.

And when you back off from the spirited driving, the MX5 shows another side. A relaxing tourer, harking back to the old open-top British and Italian sports cars it was modelled after. With the no-nonsense manual soft top down you’ve got the sights, sounds and smells of the surrounding area right in there with you. It becomes a car where everything slows down, where you can imagine drinking in some spectacular mountain roads with your partner or best friend beside you, just enjoying the experience of being out in the open.

This is the result of a car with solid fundamentals, you can take advantage of its balance and perfectly weighted controls or settle in for a relaxing ride. On the right road, in the right conditions, you start doubting you need anything more. Those who find their thrills bouncing off the limiter and searching for the limits of adhesion on every corner may need convincing but you should at least try an MX-5, as the Americans say – ‘Miata Is Always The Answer’.

What made Mazda’s special little car the bestselling sports car in the world back in 1989, is probably more relevant today than it ever has been and indisputable proof you don’t need big power to have fun. Unfortunately, it looks like we’re heading towards an automotive dystopia, with speed cameras on every road, black boxes fitted to govern speed and who knows what else? Tax per mile? A cap on annual usage?

We came to the flowing roads around the Cat and Fiddle in the Peak District with the deliberate purpose of finding out if you can still have fun within the speed limit. My answer is an emphatic yes but it takes a look back to a car of the past to get that answer. Huge power, massive grip and cosseting refinement will leave you cold and frustrated. For some of us, newer is always better but when new cars don’t play by the same rules as they did back in 1993, sometimes you need to look back to the future.

Battle of the Audi RS4 Generations: Group Test Review of the B5, B7, and B8

Few cars offer as much space and pace as Audi’s omnipotent RS4. But with prices of the first three generations now within touching distance of each other, which is the one to drive, and which is the best to buy? A throwback to one of our first articles, “The Space Race” was captured in some very trying conditions. In other words, perfect RS4 weather.

Rain. Sometimes it’s therapeutic, often cathartic, but today it’s downright maddening. The clouds above have gone through fifty shades of grey, delivering everything from fine drizzle to Hard Rain. Only Ben, our photographer, rivals the persistence of the precipitation, but even he’s beginning to lose all feeling in his fingers.

You might think these are the days when a Quattro-equipped Audi would shine, but right now, we’re half-expecting Noah’s Ark to pass on the inside. Tread depth and bravery have become the key measures of performance, not bhp and lateral G. Still, most performance cars would have long packed up and gone home. But who are we to deny a couple of V8s and a pair of turbochargers a chance to sing in the rain?

The origin of the high-performance estate is up for debate, but few manufacturers have cornered the market like Audi. Volvo made a strong bid in the mid-nineties with the T5R, but for all its image-redefining touring car chic, it never troubled the rear view mirror of an RS2 – the turbocharged uber-wagon that laid the template for the RS4. The RS2 famously outpaced a McLaren F1 – to 30mph, at least. The RS badge then migrated to the A4 Avant and later the RS6, but the ability to humble supercars remained. Just as the dictionary says ‘see BMW M5’ under the definition of a super saloon, Vorsprung Durch Technik is synonymous with plastering the family hound to the back window.

The RS2, born in 1994, was the offspring of a joint venture between Audi and Porsche. Audi provided the donor S2 Avant, while Porsche stamped its mark on the brakes, chassis and power delivery. Open the bonnet of an RS2 and you’re greeted not by Audi’s four rings, but by Porsche’s iconic typeface. Porsche’s engineers were justifiably proud of extracting 315 bhp from the S2’s turbocharged 2.2-litre inline-five – a 50% increase, thanks to a bigger KKK turbo, new intercooler, uprated engine management, larger injectors, and a freer-flowing exhaust. To cope, the suspension was lowered by 40mm, and Porsche fitted its own 17” Cup alloys from the 964 Turbo, hiding four-piston Brembo callipers.

Porsche’s plastic surgeons gave the bodywork a subtle nip/tuck, adding a Carrera-inspired front bumper, wing mirrors, and an extended rear light strip. With a 0-60 time of just over four seconds and a top speed of 160mph, the RS2 was a hit. Audi initially planned for only 2,200 units, but demand pushed another 700 out of Porsche’s specialist Rossle-Bau factory. Pedigree doesn’t come much finer – both the Porsche 959 and Mercedes 500E came out of the same finishing school. Unfortunately, only 180 of those were right-hand drive, and their rarity today puts them well beyond the reach of Rush’s little black book.

The RennSport badge returned with the RS4 in 1999. This time, Audi’s in-house go-faster arm, Quattro GmbH, teamed up with a certain British concern by the name of Cosworth, to build a monster. Their goal? An Avant capable of humbling a Porsche 911. And if BMW’s M3 got in the way, it would just have to be steamrollered too.

Starting with the already-capable S4, which had a 2.7-litre, five-valve-per-cylinder twin-turbocharged V6 producing 265 bhp, Cosworth’s engineers went to work. They replaced the cylinder head with their own aluminium design featuring enlarged intake and exhaust ports, swapped the turbos for parallel Borg Warner K04s, and increased the intercooler capacity. Stronger connecting rods, dished pistons, a recalibrated ECU, and a bigger exhaust completed the transformation.

Audi conservatively rated the B5 at 375 bhp and 325 lb-ft of torque. But the Cosworth engine was so over-engineered and receptive to tuning that the B5 became Germany’s answer to the Nissan Skyline GTR. German aftermarket tuners had a field day, and today a standard B5 is as rare as an RS2. This particular example, pristine in Nogaro Blue, recently laid down a 500bhp marker on the rolling road.

Harnessing that power is the Torsen central differential, splitting torque 50:50 between the axles under normal conditions. Massive 14” discs with double-piston callipers deliver immense stopping power – an emergency stop from 60mph takes just 2.5 seconds. Refereeing the action are 255-section tyres on beautiful, if slightly bend-prone, 18” multi-spoke alloys.

The B5’s footprint is compact by today’s standards, but it exudes discreet menace. The front air valances, rear arches, and wider track give it an unmistakably purposeful stance. At the rear, the chunky bumper visually lowers the car, while perfectly-proportioned twin oval exhausts jut out just-so.

Inside, the design is typically Germanic – dark, sober, and uber funktionell. The plush Recaro bucket seats with embossed RS4 emblems and glossy carbon fibre dashboard inserts add some much needed personality, elevating the ambience over regular A4s. Slim A-pillars and a large glasshouse means visibility is excellent, and a quick glance over the shoulder confirms the load capacity is certainly generous enough for plenty of sports car drivers ego’s.

Contemporary road tests weren’t as favourable to the B5 as they were the E46 M3 and 996 Porsche 911, citing a lack of ultimate body control and a brittle ride at odds with one another. These smaller rivals were more responsive and fleeter of foot, but here’s the rub – despite its obvious flaws, the B5 is one of those cars that gets right under your skin. Its laggy turbo delivery – no doubt exaggerated by this modified example – gives it an old-school charm, where the lack of linear throttle response is easily forgotten as your adrenaline spikes in tandem with the boost pressure. Assuming you’re north of 3,000rpm, it doesn’t matter what gear you’re in, the V6 answers and the pull doesn’t stop until the 7,000rpm limiter.

Yes, the rear axle squats comically under acceleration, the front dives under braking, and the tyres lean too hard on their sidewalls as the body rolls during hard cornering, but you can press-on safe in the knowledge that the Quattro system has your back.

Cornering the B5 is all about managing entry speed – the chassis is too surefooted for playfulness, though the steering offers more feedback than the armchair critic might suggest – it might not be geared for instantaneous turn-in, but there is genuine feedback in play. The brakes are harder to modulate, almost as if eighty percent of retardation is offered within the first couple of inches of travel, and the six speed manual serves up a knotchy throw that isn’t helped by the stubby gearlever. This lack of harmony across the controls proves to be the bigger bugbear of driving the B5 hard than any shortcomings of its chassis.

Of our trio, the B5 feels closer in character to the RS2 than its successors. But that doesn’t mean it’s antiquated. On the contrary, it feels alive at saner speeds on the public road, at a pace at which modern performance cars are still cosseting and isolating their occupants. With the B5, Audi cemented its reputation for building turbocharged, supercar-humbling estates. Yet there was no immediate successor. The RS4 badge skipped the B6 generation entirely, leaving a four-year gap that saw Audi rethink its formula. When the RS4 finally returned, it came back with a bold shift in philosophy – gone was the turbocharged surge, replaced by a high-revving, naturally aspirated V8.

Stealing M Division’s thunder, the 4.2-litre quad cam V8 developed its 414bhp at a spine-tingling 8,250rpm. The engine was so good, it later went on to power Audi’s first mid-engined sportscar, the R8. Further tweaks brought the B7 into closer alignment with the M3; the Quattro system was adjusted to favour the rear axle, sending sixty percent of power aft, and the front wings were now fashioned from aluminium to reduce weight over the nose, improving turn-in. With a slick manual gearbox, discreetly flared arches and surprisingly talkative steering, the B7 RS4 had morphed from a turbocharged bruiser to a precision instrument, burning off wooden handling Audi stereotypes faster than it sprinted from 0-60mph.

I’ve had extensive previous exposure to the B7, but as I drop into the driver’s seat I don’t recall it being mounted so low. Nor do I recall the embrace from the wingback Recaro clamping my waist tight enough to have me thinking cancelling that gym membership was a bad idea. The flat bottom wheel looted from the Lamborghini Gallardo looks fantastic with its perforated leather. The same material is carried over to the stubby gear lever, whilst the aluminium effect pedals are perfectly spaced. With its minimalist design, flashes of carbon and dials backlit in red it’s a classy interior that instantly makes the B5 feel the two generations older it is.

But the real step up in the B7 is in the driving – it takes all of fifty yards to know the B7 is a significantly different prospect from what came before. Where you feel your way into the B5, building up the pace, in the B7 you’re already eager to press on and it’s a key difference. You notice it first in the powertrain, which has none of the slack present in the B5. Throttle response is instantaneous and the clutch is lighter whilst the wonderful gear change slots home ratios with slick, oily precision. Then there is the damping – it’s firm at low speed but never jarring, taking on a wonderful fluidity with speed as it smooths off the harshest imperfections in the road, yet always maintains rock-solid body control. It should be stated that owner Mark has fitted some KW coilovers in place of the notoriously leaky and expensive DRC suspension, but it’s a sweetly judged, OEM+ package.

The steering has less initial weight than the B5 but loads more naturally. Confidence floods back into your forearms from the perfectly judged gearing, and you soon completely trust the car to go exactly where you tell it to when you tell it to. There is certainly more finesse and precision to the way the B7 handles, and come to think of it – stops, courtesy of this cars’ ultra-rare optional carbon-ceramic brakes. And that’s before I press the Sport button, which brings the additional benefits of an even sharper throttle and even more wind knocked out of me as the side bolsters inflate. It also opens the valves in the aftermarket Milltek stainless steel exhaust due to some cheeky coding by Mark.

Acceleration is an altogether different topic. Jump straight from the five into the seven and you’ll immediately ask where all the power has gone. It’s still there, this particular B5 has just warped your perception of speed. But it’s also twisted your perception of shift points. At 5,000rpm in the B5, you’ll be considering another gear, content to bask in the absolute mountain of torque, whereas the B7 will just be getting into its stride. The V8 thrives on revs and Mark tells me the more time spent above that marker is a good thing, his official line being it helps to prevent the known carbon build-up issue – as if I needed more encouragement to venture north of 8,000rpm. Wind the B7 up to its redline and you’ll have no doubt it’s a genuine 170mph car, sans limiter.

Mark’s smitten with the B7. ‘Next year I’m taking it to the Nürburgring to experience its full potential, where those carbon ceramics should come in handy. You’ll never find me complaining about this car no matter how much of my money it demands. The spec made this car irresistible – unique paintwork, double glazing, solar roof, and those wingback Recaros make it feel special even compared to most modern cars. In my opinion, the car still looks as good as most cars coming out of the factory today, but if you are interested in owning a B7 make sure you have deep pockets because the parts prices come at a premium.’

It’d be worth it though. The B7 remains a coveted car today and, after the R8, is arguably Audi’s greatest driver’s car – 20v UrQuattro included. It was even available as a saloon and a chunky cabriolet this time around, making the B7 the only RS4 to experiment with other body styles. However, neither holds the same cachet as the Avant, which remains the definitive RS4 silhouette.

Clearly, the B8 RS4 had a tough act to follow. Introduced in 2012, the B8 retained the same 4.2-litre V8 from the B7, but output increased to 444bhp. Torque remained at 317lb-ft, but crucially, it arrived 1,500rpm sooner – at 4,000rpm – and was sustained to 6,000rpm. Combined with the rapid-fire shifts of a 7-speed dual-clutch transmission, the B8’s straight-line performance was taken to another level – from standstill, the B8 RS4 will hit 100mph in just 9.4 seconds – rain or shine. But despite the boost in power, the driving experience, for many, felt like a step backwards.

In a reversion to type, Audi dropped the ball with the B8’s steering, swapping the acclaimed hydraulic assistance of B7 for an electro-mechanical setup, which, while improving efficiency, came at the expense of feel. The steering, too light and quick, stripped away a key layer of engagement, as did the loss of the manual gearbox. Audi had once again pivoted with its philosophy for the RS4, moving it away from the M3 and pitching it as more a junior RS6, more interested in crushing continents than the backroads of the Yorkshire Dales. The pivot can be partially explained by the introduction of the RS5 coupe, which now targeted the BMW.

That doesn’t mean Audi Sport didn’t put the effort in. As well as producing the goods, the V8 was mounted further back in the RS4’s chassis, although the bulk of its mass still resides ahead of the front axle. Nevertheless, it was enough to have a useful effect on the weight distribution, which had shifted from 60:40 in the B7 to 56:44, whilst the wheelbase grew by 162mm and the tyres swelled to 265 section all round, increasing grip and improving stability. Speaking of distribution, the Quattro system retained the B7’s 40:60 split in normal driving, but under duress, up to 70 percent of drive can go to the front or 85 percent to the rear. The system also gained a crown gear centre differential with selectable drive modes and torque vectoring.

The B8 also offered far more than the rudimentary Sport button of the B7. Calibration options extended to the gearbox, steering, dampers, exhaust, and throttle mapping. Thankfully, owner Rich is on hand to navigate the labyrinth, settling on comfort steering, auto damping, and dynamic settings for the throttle, differential, and exhaust, with the gearbox in full manual.

Even set up as such, the B8 can’t fully let go of its inhibitions. The speed is massive – too quick for the B7 along the straights, too grippy for the B5 in the corners – but it remains far too civilised producing it and the steering too inert, there is little sense of connection to the road, or of the limit of adhesion. The wide track, lack of roll and artificially quick steering do mean you can chuck the B8 into low-speed corners and direction changes with the same abandon as the B7, but outright pace is the only reward.

The tune coming out of those fat, signature oval pipes also remains slightly too subdued for our liking, but to be fair, we must remember today’s B7 has an aftermarket system fitted. The response to even minor throttle applications however, is deeply impressive – it’s a shame this derivative of the V8 never found its way into the R8 alongside the V10.

The brakes – eight-piston callipers & 365mm discs up front – are another talking point, but thankfully not down to their performance, which is impeccable. The curiosity comes from the unique flower petal design of the discs in order to better dissipate heat. Beware, however, their wavy circumference means a £2,000 bill come renewal time. Suddenly the £6,000 factory carbon ceramics don’t look so pricey.

As a pure driver’s car, it’s plain to see the B8 falls short. But that doesn’t mean all is lost. The B8 is comfortably the most comfortable car here, the build quality is vault tight and the interior is a wonderful place from which to while away the miles. There is a subtle, timeless elegance to the exterior design that gives the B8 a slow-burn ownership prospect appeal, one that would sit perfectly in a two car garage with something more exciting to drive on the weekends.

Audi has recently confirmed the current B9 generation RS4 will be the last. The outgoing model has seen the RS4 come full circle, returning to a 90 degree, twin-turbocharged V6 – a unit borrowed from none other than Porsche. This time the capacity is 2.9 litres and whilst the headline bhp is only up a fraction to 450, the torque has multiplied to 442lb-ft. Thanks to the blowers, the B9 makes its numbers over a much greater duration of the rev range, meaning acceleration has taken another quantum leap forwards. With its fast-acting ZF 8 speed automatic, the RS4 is comfortably sub-four seconds to 60mph, yet is capable of over 30mpg, two statistics the V8 cars can only dream of.

Disappointingly, we had a very special B9 RSR lined up to take part today, but Covid-19 quarantine restrictions intervened. Rest assured we’ll bring the car to these pages in the near future. Until then, which is our favourite RS4?

By any tactile measure the B7 is the undisputed winner. It’s an Audi that legitimately went toe to toe against the M Division with the added benefits of 24/7 any-weather security, Avant practicality and an engine that wouldn’t disgrace a Ferrari. It is exactly what an RS4 should be – practical performance and dynamic engagement rolled into a single package.

However, once the rain clouds have cleared and the feeling has returned to snapper Ben’s fingers, it’s the B5 that lingers longest in the memory. If the B8 is the GT and the B7 the communicator, the B5 is the beast. The original RS4 just has a greater sense of mischief about it that keeps you coming back for more, a turbocharged charisma that isn’t solely down to the adrenaline fuelled 500bhp performance of this example. Or perhaps, in this case, absolute power does corrupt absolutely.

Engine Specifications and Power Outputs

| Specification | B5 RS4 Avant | B7 RS4 Avant | B8 RS4 Avant |

| Engine Type | 2.7L V6 Biturbo | 4.2L V8 Naturally Aspirated | 4.2L V8 Naturally Aspirated |

| Power Output | 380bhp @ 7,000rpm | 420bhp @ 7,800rpm | 444bhp @ 8,250rpm |

| Torque | 440Nm @ 6,000rpm | 430Nm @ 5,500rpm | 430Nm @ 4,000–6,000rpm |

Performance Statistics

| Metric | B5 RS4 Avant | B7 RS4 Avant | B8 RS4 Avant |

| 0–60mph | 4.7 seconds | 4.7 seconds | 4.7 seconds |

| 0–100mph | 11.3 seconds | 11.4 seconds | 11.4 seconds |

| Top Speed (lim.) | 155mph | 155mph | 155mph |

| 1/4 Mile Time | 13.2 seconds (108mph) | 13.0 seconds (109mph) | 12.9 seconds (110mph) |

Transmission and Drivetrain

| Specification | B5 RS4 Avant | B7 RS4 Avant | B8 RS4 Avant |

| Transmission | 6-speed manual | 6-speed manual | 7-speed S-Tronic dual-clutch |

| Drivetrain | Quattro AWD | Quattro AWD | Quattro AWD |

| Torque Split | 50:50:00 | 40:60 (front:rear) | 40:60 (front:rear) |

Chassis Information

| Specification | B5 RS4 Avant | B7 RS4 Avant | B8 RS4 Avant |

| Front Suspension | Independent multi-link | Independent multi-link with DRC | Independent multi-link with DRC |

| Rear Suspension | Double wishbone | Independent multi-link with DRC | Independent multi-link with DRC |

| Front Brakes | 360mm ventilated discs | 365mm ventilated discs with 8-piston calipers | 365mm ventilated ‘wave’ discs with 6-piston calipers |

| Rear Brakes | 312mm ventilated discs | 324mm ventilated discs | 330mm ventilated ‘wave’ discs |

Weights and Ratios

| Specification | B5 RS4 Avant | B7 RS4 Avant | B8 RS4 Avant |

| Kerb Weight | 1,620kg | 1,650kg | 1,795kg |

| Power-to-Weight Ratio | 234bhp/tonne | 255bhp/tonne | 247bhp/tonne |

| Torque-to-Weight Ratio | 272Nm/tonne | 260Nm/tonne | 240Nm/tonne |

| Weight Distribution | 58% Front / 42% Rear | 58% Front / 42% Rear | 56% Front / 44% Rear |